Palate Savvy/Sud de France Instagram Live Broadcast: Gaillac

Occitanie, the administrative region in France that covers a good portion of the country’s southwest, from the right bank of the Rhône River to the east, to the eastern edge of Aquitaine to the west, contains several wine-producing zones that remain relatively unknown. It’s hard to put a finger on which part would qualify as the most underappreciated – so many excellent wines come from here, whether or not one takes price into account (alas, a few too many mediocre ones, too, though modest pricing offers some compensation). But, for the missed opportunities for excitement of those who remain unaware, Gaillac certainly belongs near the top of the list.

While identified as a ‘Southwest’ wine region, Gaillac is in fact wedged between the Southwest and the Languedoc, and might almost be understood as belonging to a group of appellations that one might dub “Mediterranean-Atlantic,” including Limoux, Cabardès, and Malpère. I say “almost,” since Gaillac is over an hour drive between the Languedoc portions of this coterie. Still, Gaillac takes on as much of the heat from Mediterranean as the freshness the trio I’ll dub “LCM” enjoys from the Atlantic. That Gaillac has as many, perhaps more, olive trees than can be found in LCM is telling. (NB – This is a purely anecdotal observation. I don’t know how many olive trees there are – but I do know that there are far fewer oliviers here than in other parts of the Languedoc, and at least one farmer in Gaillac just planted a bunch).

Beyond the confluence of Atlantic and Mediterranean climates (and, according to the metéo – Gaillac is warmer today than the LCMs), Gaillac’s greatest attribute is diversity: diversity in soils, diversity in wine styles, and diversity of grapes

I’ll get to that in a moment, but first a little history lesson (surprise). Gaillac, as many other places in southern France, has the Romans to thank for their wine industry. Records show that vines were planted, and wine was made here for commercial purpose from the first century BCE, though likely the history is a bit older. A part of the Roman province of Narbonnesis that extended from the Rhône Valley to the east to about 50 kilometers west of the present town, Gaillac was recognized as being one of Gaul’s grand crus. As in most of the rest of France, the fall of Rome brought with it the rise of the Church and vines served both heavenly and earthly purposes. Crusades – the Albigensian crusade against the Cathar movement was so named after the Gaillacaise town of Albi that was a center of Cathar activity (a complicated story that will discussed at another time. For now, understand that Cathars were an anti-materialist, dualist movement that eschewed the corruptions of the physical world in favor of a pure reality of the spirit. The worldly Church didn’t take kindly to the implication and declared a crusade against the heretics in 1204 . French king Philippe II, who saw the advantage of taking down the Toulouse-based ruling nobles who supported the Cathars, slowly jumped in – he was otherwise busy battling the English – followed by his son Louis VIII. The Cathars lost, either killed, went underground, or forced into cruel repentance) did Gaillac winemakers no favors (more than a few suffered death and a lot worse). Yet, while traumatized by the experience, Gaillac got by through the fortune of favor its wines enjoyed by the English court – which effectively ruled much of southwest France from the first third of the fourteenth century until the end of the (bit longer than) Hundred Years’ War in the middle of the fifteenth. English taste for Gaillac wine was reestablished at a 50 wine keg bacchanal François I threw for Henry VIII in Calais in 1520, though, of course, historical events closed and reopened the tap several times in subsequent years, decades, centuries.

Difficulties in the international market or not, Gaillac’s wines had a reputation that needed protection, particularly against counterfeiters from the outside attempting to pass their mediocre, or adulterated wines off as noble Gaillac. While controls were difficult to enforce, the local wine producers, supported by the local aristocrats that lorded over the territory, established certain quality standards, among which was the interdiction of importing and therefore, blending wines from the outside with those produced within Gaillac’s realm, the exclusive use of pigeon manure to fertilize vineyards, and the obligation to stamp a cockerel logo on every cask of Gaillac wine exported from the territory. That symbol is still in use today.

With 3200 hectares (7900 acres) in production for appellation-certified wines (others including IGP, bring to total planted area to 6800 hectares), makes Gaillac one of the largest appellations d’origine protégées in Occitanie, following Corbières, Minervois, and Côtes du Roussillon in the Languedoc-Roussillon.

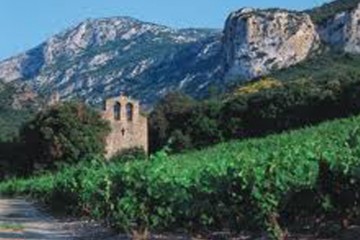

Abord the banks of the Tarn River, the appellation has three distinct terroirs: the terraces on the left bank of the river with soils composed of round stones (galets roulés) sand, and graves; the hillsides on the right bank that are largely clay and limestone; and a plateau of limestone above the right bank. Another zone of schist also exists to the east of the town of Albi, in the direction of the Languedoc.

The variety of grapes is astounding, especially given the fact that many of them are not found elsewhere. Among reds is Prunelart, Braucol (synonym of Fer aka Fer Servadou aka Mansois aka Pinenc aka…), Duras, Syrah, Gamay, Merlot, and the Cabernets. Among whites are Ondenc, Loin de l’œil (Len de l’El), Mauzac Blanc, Muscadelle, Sauvignon Blanc, and Sémillon.

Okay, you say that’s a good number, but except for four of the grapes: Prunelart, Duras, Ondenc, and Loin de l’Oeil, the others are found elsewhere. True. But, those are the grapes that were authorized for Gaillac AOP when the rules were made some decades ago, that is, when considerations such as economic viability and scale of production were primary. In fact, there is a whole menagerie of historic, Gaillac-only cultivars that have garnered increased intention in recent years, started largely by the efforts of Robert Plageoles, followed by those of his son Bernard at their eponymous family estate Domaine Plageoles. In the 1970s Robert Plageoles took upon himself to work only with autochthonous grapes, the four mentioned above, plus…(get ready)…Verdanel, seven types of Mauzac (Blanc, Noir, Vert, Gris, Rose, Roux, and one I can’t figure out. On a visit two years ago, Bernard told me about seven, but I clearly didn’t write quickly enough, and his website only shows six), Jurançon Noir, Prunelart Blanc (and I was excited about Prunelart Noir), Piquepoul Gris, Piquepoul Noir (which is a grape permitted in Châteauneuf-du-Pape), Morrastel (which is likely the same as Graciano in Spain), and two I’ve never heard of: Mourtes and Marocain Gris. Finally, there’s one for which I have special affection: Nehelescol, otherwise known as Géant de Palestine, which was identified in the Hebrew Bible as the giant grapes Moses’ spies saw being carried on a litter in the Land of Canaan.

While the Plageoles might have been outliers in the 1970s, they are certainly far from that today. Whereas the trend in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s had distinctly been toward ‘international’ grapes like Sauvignon Blanc, Cabernet France, and Merlot, more attention is distinctly given to the indigenous varieties, especially the Loin de l’Oeil, Ondenc, Braucol, and Duras. The more obscure ones have their partisans, many of them acolytes of the Plageoles. It seems almost unnecessary to say it, but for these producers, vineyard and winemaking practices veer toward the natural side of things, with relatively little intervention on the vines and in the winery. Wines not made with authorized grapes – no matter how ancient their local provenance, are classified as IGP (Vin de Pays) du Tarn, or Vin de France. Of the latter, depending on one’s perspective, one might thrill to, or be repulsed by the potential array of unexpected aromas and flavors, including an occasional hint of volatility. I fall firmly in the thrilled camp – but not always, and I am delighted by the range of producers who work with great attention to clean viticultural practices, who also know how to add some polish, too.

The vastness of possibilities in Gaillac wines extends to wine styles, too, which is possible unparalleled in any appellation of France. Dry reds whites, and rosés are the norm, ‘traditional’ as well as a nouveau style made from Gamay in the style of Beaujolais nouveau. But there are also three styles of sparkling wine: so-called méthode gaillacoise, aka, méthode ancestrale (found in Languedoc’s Limoux, too), méthode traditionnelle (or the classical or ‘Champagne method, méthode champenoise, a term though, not the method, applicable in Europe only to wines made in the Champagne region), and perlé, a fresh, tingly wine with slight effervescence derived traditionally from bottling a dry, light wine just before alcoholic fermentation has ceased, or more usual today among more commercially expedient producers, by dosing a dry white with a touch of CO2 . Then, there is the vin de voile, a dry white aged under a blanket of flor, a yeast stratum that can insulate white wine resting in a not full barrel, much like Spain’s fino sherry or the Jura’s vin jaune, then left to oxidize, and finally, a sweet wines, mostly white, but also red, too. Ah, and there is some superb eau de vie made here, too, including that of Domaine Cazottes, who ranks among the best distillers in France.

Some Gaillac producers to look for (not at all complete)

“Classicists”: Domaine du Moulin (possibly the most dynamic Gaillac producer on the market today, Nicolas Hirissou is noteworthy for his finally crafted wines, organic viticulture – which has become common in the area, his new olive plantings, and, not the least, his passion for falconry – or in his case, eaglery.), Domaine Rotiers, Domaine d’Escausses, Domaine des Terrisses, Domaine Gayssous, Domaine Sarrabelle, Domaine de Borie-Vieille.

“Natural”/Avant gardistes: Domaine Plageoles, La Ferme du Vert, Domaine de Causse Marine, L’Enclos des Braves, Domaine de la Ramaye, Domaine Cazottes, Domaine Philémon,

Books should be written about the glories of Gaillac – perhaps a project for the future – but for now, I invite you to enjoy a brief video Instragram Live Broadcast taking place on Friday, April 17, at 1pm (19h France, 10am California) on the Sud de France NY Instagram page: @suddefranceny. The video will be up for 24 hours, then, hopefully, it will be available elsewhere. Maybe here.